Reducing Bugs by Using the Model View Update Pattern

Note: This article is part of the 2025 C# Advent Calendar, so after you're done reading this, keep an eye out for the other cool articles coming out this month!

For those who've followed me for a bit, you know that I'm a big believer that functional programming is a great way of approaching problems.

One thing I've mentioned in my recent presentations is that we can take introductory concepts (pure functions, immutability, composition) and build real world software with them.

In this post, I'm going to show you a pattern that I've recently ported to C#, the Model View Update, also known as The Elm Architecture.

Inspiration of the Pattern

Back in 2017, I came across a new functional language called Elm that took a different approach for web development. At a high level, Elm argues that you can think of an application as four pieces.

- The Model - What data are we presenting to the user?

- The View - How should we format the model?

At this point, this seems very similar to other MV* patterns (Model View Controller, Model View Presenter, or Model View ViewModel).

The next two parts is what sets this pattern apart from the others.

- The Command - What things can the user do on the screen (button clicks, entering text, etc...)

- The Update function - Given a Model and a Command, what does the new model look like?

To me, this is an interesting concept because when the user makes changes, the model is being directly manipulated (generally through two-way binding) and then you had to make sure that you didn't put your business rules directly in the UI code. (For those who come from WinForms, how many times did you find business code in the code-behind?).

With this approach, however, we've narrowed down what the UI can do (it can render a model and return a command, but can't directly manipulate the model).

If you think that this approach isn't solid, you might be surprised to know that Elm inspired the creation of the following libraries in the JavaScript ecosystem:

I've recently been using this pattern for console applications and have been pleasantly surprised how well it's working out.

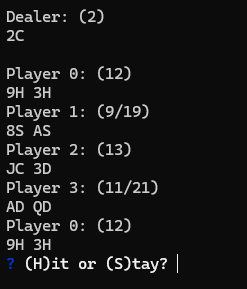

In this post, I'll walk you through how we can use this pattern to build out the "Hello World" equivalent application, manipulating a counter.

Implementing the Pattern

Defining the Command

Before we can model the Command, we need to think about what commands we want to support. In our example, let's say that we want the user to be able to do the following:

- Increment the counter by 2

- Decrement the counter by 1

- Reset the counter to 0

- Quit the application

In the Elm version (and it's equivalent TypeScript definition), a Command looks something like this:

This takes advantage of algebraic data type known as a sum type, where the Command type has one of three different constructors (one called increment, another called decrement, one called reset, and finally, quit).

Even though C# doesn't have sum types (at least not yet), we can mimic this behavior using an abstract class.

Defining Commands for Counter

With the Command class defined, let's start implementing the various commands our program can have.

First, we'll define an enum to keep track of the types of Commands. We could omit this and just use strings, but the value of the enum is that we can have C# generate the cases (though we still have to have a default case given the nature of enums).

With the enum defined, we can start define the commands, some of which will have more information included (see the IncrementCommand and DecrementCommand).

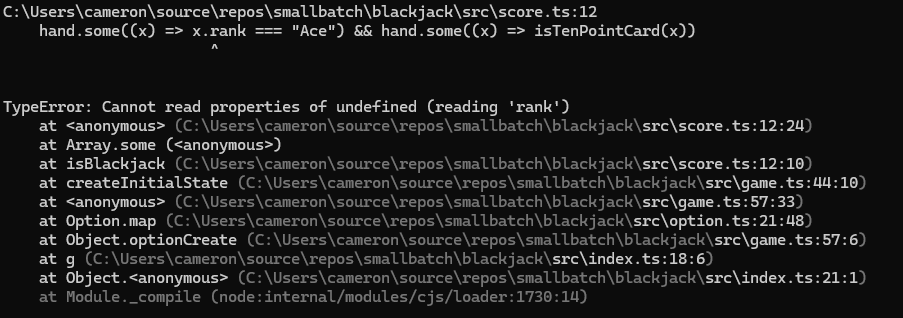

Implementing the Update Function

Now that we have our various commands created, we can start building out the Update function.

From our earlier description, we know that our Update function has to take in our model (a number) and a Command and then has to return a new model (a number).

Implementing the View Function

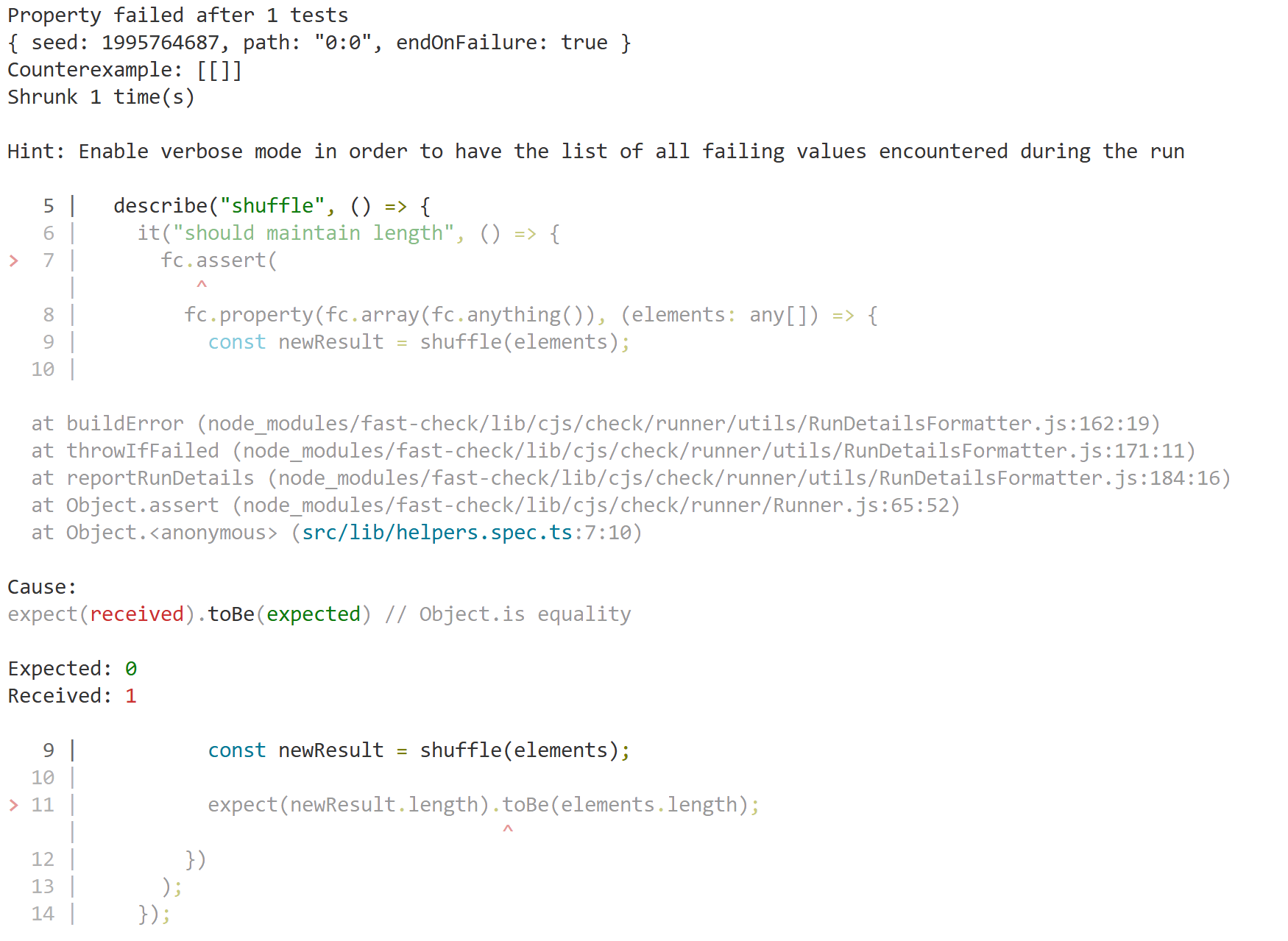

At this point, we could go ahead and start writing tests to verify that our model is being updated given the command, but our users are going to be interacting with the application, so let's build that out next.

From before, we know that the View function takes in the model (a number) and it will return a Command. Given that we need to interact with the user, this is an impure function by design, so we shouldn't put our business rules in here.

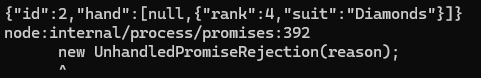

Wiring Everything Together

Now that we have our Model (a number), the View function, an Update function, and our list of Commands, we can wire everything together.

Final Version

With the Framework.Run function defined, we can invoke it via our Program.cs file.

You can find the working version below (or you can clone a copy from GitHub)

Conclusion

In this post, we built out a basic application using the Model View Update pattern that was first introduced by the Elm language. We also implemented a basic sum type, Command, using an abstract class that was then constrained to particular CommandTypes.