Mars Rover - Intro To Testing

What This Is and What This Isn’t

The goal of this post isn’t to try to convince you that you should be unit testing your code, but to give you enough information that if you need to unit test your code or if you’re in a codebase that expects tests, you will have the knowledge to hold your own. If you are looking for reasons why you should be testing, there are some great resources in the Additional Resources section at the end of the post!

Unit Testing 101

At its core, unit testing is the practice of writing code that tests that your code is working correctly. Confused? It’ll make sense in a minute, I promise! If you’ve ever made changes to a project, how confident were you that your changes worked? If I had to guess, there’s a high level of confidence that your changes solved the problem. However, how confident were you that your changes didn’t break some other piece of functionality? I imagine that your confidence is a bit lower. For me, I’m reasonably confident that my changes are solid, but I’m not always sure that I didn’t break some other features elsewhere. The most straightforward approach to verify everything is working correctly is to run the application and try it out, right?

For small applications, that’s a pretty reasonable approach to take and wouldn’t take too much time. However, what if you’re working on a more complicated application? How much time is it taking for you to compile the application, launch it, and start navigating through the UI? The premise of unit testing is that we can exercise the same logic that’s running in the application but without having to go through the interface. This type of testing is generally faster and less error-prone since your test code will do the same tests over and over again. The downside is that you’ll spend more time writing code, but for me, I feel much more confident in my work when I can run the full test suite and know pretty quickly if I’ve broken something.

Naming Again?!

If you’ve been following along with the Mars Rover kata series then you know I’m a huge fan of using the same language as my Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) when it comes to the problem at hand as it prevents confusion when different terminology is used for the same concept.

When it comes to naming my tests, I take this approach one step further and name my tests in such a manner that if you read the class name followed by the method, then you’ll have a clear idea of what the test’s intent is. The main reason I name my tests this way is that if my test fails, I want to know what requirement or workflow is not working so I can see if it makes sense for that workflow to be impacted.

Sometimes, a test will start to fail because requirements have changed, so the test needs to be updated or removed. In other cases, the test failure reveals a contradiction in rules so it helps me if I can clearly see the use case and ask the right questions to my SMEs.

Framing Context with Given/When/Then

When it comes to naming my test classes and method, I borrow inspiration from the Given/When/Then naming methodology. I came across this convention when learning about Behavior Driven Development (BDD) early on in my career but I was familiar with the naming convent from working with user stories. The intent of Given/When/Then is that it provides the context, an action, and a result. Going to Mars Rover, an example user story would be

Given that the rover is at (0, 0) facing North, when it receives the move forward command, then it should be at (0, 1) facing North

Let’s break this user story down and examine the various parts:

Given

The Given portion of the user story sets up the context of the application. It can be as simple as Given that the user is logged into the system or as complex as Given that today is a holiday and that a user wants to make a reservation. The goal here is that someone can read this portion of the story and understand what is being accomplished. For this user story, the context is that we have a Rover that’s located at (0, 0) facing North.

When

The When portion of the user story gives what action is being taken in the application. At this level, we’d typically stay away from technical jargon (i.e. the user clicks the reservation button) and focus more on the workflow being accomplished. For this user story, the action is that the Rover received the Move Forward command.

Then

The Then portion of the user story tells us what the expected result or behavior is. It can be as simple as then the total is $42.55 or as complex as then the sale is declined and the user is informed that there was an issue processing the payment. For this user story, we’re expecting that after the Rover receives the Move Forward command, then the rover is at (0, 1) facing North.

Test Structure and Naming Conventions

Now that we’ve learned a bit more about Given/When/Then, let’s talk about how this can influence your test structure. When I’m writing tests, I’ll typically place them in a unit test project that’s separate from production code so that we don’t deploy the unit tests with the production code.

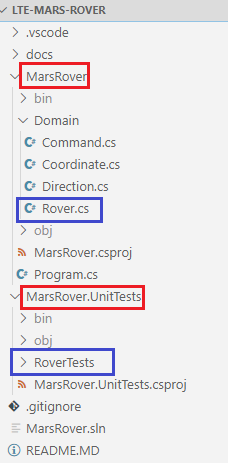

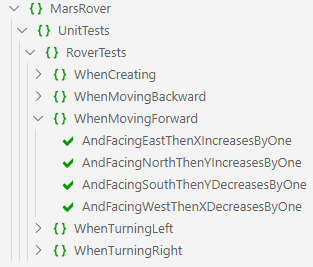

In the case of Mars Rover, if I have a project called MarsRover, then I’d have a project called MarsRover.UnitTests. Once I have this new project created, I’ll create a folder called xyzTests where xyz is the name of the class I’m writing tests against. So if I’m writing tests against the Rover class in the MarsRover project, then I would have a folder called RoverTests in the MarsRover.UnitTests project.

From here, I’ll generally create a file per method or workflow that I want to test for the class. So based on our user story above, I would have a file called WhenMovingForward and this file will contain all the different tests for this functionality. Once a file is in place, we can start writing the various test methods for different behaviors. When naming methods, I will include the context for the setup and what the expectations were. By combining the test name and the method name, it will sound like a user story.

Organizing Your Test With Arrange/Act/Assert

At this point, we have the infrastructure in place for our tests, so how do we write a good test? Every good test will have three parts, Arrange, Act, and Assert. In the Arrange step, we’re going to focus on creating dependencies and getting the initial state setup for the test. For simple tests, this step may only consist of creating the class that we’re testing. For more complicated tests, there may be more dependencies to create, some methods to call, and possibly modifying the local environment. The Act step is where the method or property that we’re testing is called. This step should be the simplest portion of the test since it should only be a line or two of code. The third and final step is the Assert step where we check that the result we observed was correct. For simple tests, this could be a single line where check a value whereas more complicated tests may need to check various properties.

Using WhenMovingForward as an example, here’s what an example test might look like.

I like to think of Arrange/Act/Assert (AAA) as a science experiment because we have to first find a hypothesis, design some test to prove or disprove the hypothesis, get all the necessary ingredients together for the test, run the test, and see if we have evidence to support our hypothesis.

Wrapping Up

In this post, we took a brief break from the Mars Rover kata to get a quick understanding of unit testing and the naming conventions we’ll be leveraging for the rest of the series! We first talked about the importance of naming and how if we follow Given, When, Then syntax, we can turn our user stories into readable test names for future engineers. From there, I showed you Arrange, Act, Assert notation for tests, and an example test using the convention. Next time, we’ll start implementing Rover!

Additional Resources

- Unit Testing Makes Me Faster (presentation) by Jeremy Clark

- Given, When, Then by Martin Fowler

- Starting to Unit Test: Not as Hard as You Think by Erik Dietrich

- The Art of Unit Testing: with examples in C# 2nd Edition by Roy Osherove

- _Everything I Needed To Know About Debugging I Learned In Elementary Physics (presentation) by Nate Taylor